This post is part of a series on privacy-preserving federated learning. The series is a collaboration between the Responsible Technology Adoption Unit (RTA) and the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Learn more and read all the posts published to date on our blog or at NIST’s Privacy Engineering Collaboration Space.

Our first post in the series introduced the concept of federated learning and described how it’s different from traditional centralised learning - in federated learning, the data is distributed among participating organisations, and share model updates (instead of raw data).

What kinds of techniques can we use to build privacy-preserving federated learning systems? It turns out to depend heavily on how the data is distributed. This post defines and explains the different ways data can be distributed, or partitioned, among participants in federated learning systems. Future posts in the series will describe specific techniques applicable in each situation.

Data partitioning schemes describe how data is distributed among participating organisations, as compared to the centralised scheme in which one party holds all the data.

- In a horizontal partitioning scheme, the rows of the data are distributed among the participants

- In a vertical partitioning scheme, the columns of the data are distributed among the participants.

Combinations of the two are also possible—we’ll get to those at the end of this post.

Horizontal Partitioning

Consider our example scenario from the first post in this series: a consortium of banks wants to train a model to detect fraudulent transactions. This is an example of horizontal partitioning: each bank holds complete transaction data (i.e. containing all relevant columns) for its customers, and it’s the rows of data that differ between the banks.

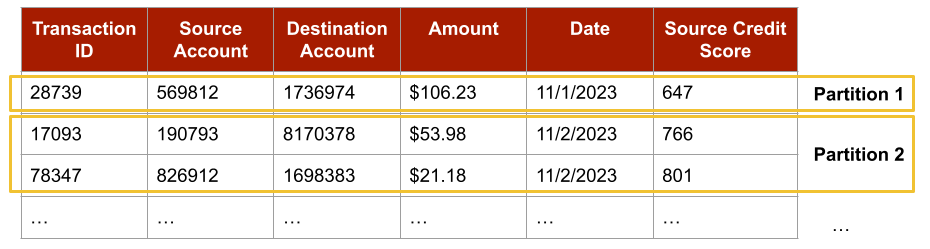

Figure 1: Horizontally partitioned data. The partitions split up the rows of the data, but not the columns. Each partition contains distinct rows, but the same set of columns. Note that the data values shown are fictitious.

Figure 1: Horizontally partitioned data. The partitions split up the rows of the data, but not the columns. Each partition contains distinct rows, but the same set of columns. Note that the data values shown are fictitious.

The term horizontal partitioning comes from the fact that the centralised version of the scenario can be transformed into the distributed version by drawing horizontal lines to indicate the different partitions, as shown in the example in Figure 1.

In general, it’s easier to build privacy-preserving federated learning systems for horizontally partitioned data than it is to build similar systems for vertically partitioned data. This is true because when the data is partitioned horizontally, each partition can be viewed as a complete dataset (i.e. there are no columns missing), which means each participant can train a model locally without consulting other participants.

Some types of models can be composed after they are trained, which leads directly to a simple but elegant approach for federated learning for horizontally partitioned data: first, each participant trains a model locally on their own data; then, the trained models are composed to form a more effective final model. We’ll discuss approaches that follow this structure in the next post in the series.

The public health track of the US-UK pets prize challenges was an example of horizontally partitioned data. In this track, data about individuals in a synthetically-generated population were distributed across a number of health districts. Each district held information about each individual such as their demographic attributes, social contacts, and infection status. Privacy-preserving federated learning across these horizontal partitions was then used to train models to predict an individual’s future risk of infection.

Vertical Partitioning

Consider an alternative scenario involving a single bank (still holding customers’ transaction data) and a credit reporting agency that holds credit ratings. The two organisations might wish to train a model that leverages both the transaction data and the credit score of a single customer. This is an example of vertical partitioning: the two organisations hold different kinds of data about the same individuals; in this case, it’s the columns of data that differ between the participants.

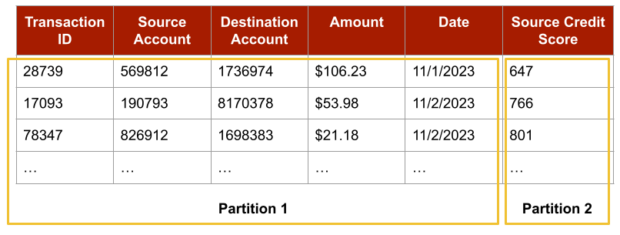

Figure 2: Vertically partitioned data. The partitions split up the columns of the data, but not the rows. Each partition contains the same set of rows, but a distinct set of columns. Note that the data values shown are fictitious.

This time, transforming the centralised version of the scenario into the distributed version involves drawing vertical lines to indicate the different partitions, as shown in the example in Figure 2.

Privacy-preserving federated learning systems for vertically partitioned data are especially challenging, primarily due to the need to link together data points from different partitions about the same individual or entity during training. In contrast to horizontally partitioned federated learning, it’s generally not possible to train separate models on different columns of the data (but overlapping rows) and then compose them afterwards.

As a result, systems for privacy-preserving federated learning with vertically partitioned data are generally more complex and challenging to build. We’ll discuss techniques for building such systems later in the series.

Combining Vertical and Horizontal

In practice, federated learning will often involve training data distributed across a combination of vertical and horizontal partitions. This was a feature of the financial crime track of the US-UK PETs prize challenges.

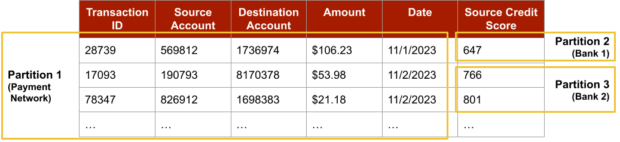

The aim of this track was to train an anomaly detection model using a synthetic dataset representing transaction data from a global payment network, enriched with synthetic account metadata (e.g. credit scores) held by banks. The account metadata was horizontally partitioned, with each partner bank storing the same metadata fields (i.e. the same columns) for each of its registered accounts.

Figure 3: Combined partitioning. The account metadata held by banks (the credit score for each account) is partitioned horizontally, and the transaction data held by the payment network is partitioned vertically. Note that data values shown are fictitious.

Each transaction held by the payment network can only be enriched with account metadata by linking on an appropriate Account ID. Banks do not have access to the transaction data held by the payment network, meaning that the data linking needs to be done in a secure and private way. Moreover, the horizontal partitioning of the account metadata means that an efficient method is needed for determining which partner bank is relevant for linking for a particular account.

This example shows that scenarios involving both horizontal and vertical partitioning bring additional complexities. In this setting, training a model that can detect fraud with high accuracy – while also ensuring privacy – is especially challenging. Future posts in this series will describe these challenges and explore some of the techniques used to solve them in the US-UK PETs prize challenges.

Coming Up Next

In our next post, we’ll begin to explore practical approaches for protecting privacy in the different partitioning scenarios described above, starting with a deep dive into input privacy approaches for horizontally partitioned data.

Recent Comments